Sorting Books the Library Way

Em Ricciardi, Cataloger

Like many of us stuck at home, I’ve been doing a lot of cleaning lately. As part of my great apartment cleansing, I decided to reorganize one of my bookcases. The question: how should I do it?

Libraries usually use standardized classification systems to organize their books. The main guiding principle behind these systems is making it easier for patrons to browse. If you go into a library looking for books on baking, you’d probably appreciate finding all the baking books together. Most of us would probably like our own bookshelves to work in a similar way. I suspect that in reality we just stuff the books wherever they fit.

My own bookcase has a pseudo-classification system which I have decided to name the SystEm. Here’s how it breaks down:

Shelf 1: Science fiction, fantasy, and fairy tales ; literature from the 21st century

Shelf 2: Mystery books ; more literature ; queer books

Shelf 3: Plays and books related to theater ; more literature

Shelf 4: Instructional books ; collectable literature

Shelf 5: Oversize and art books

This system isn’t terrible; after all, I can find books when I want to read them. But what if it could be better? What if I could apply a library system to make my bookshelf more organized? I decided to find out by sorting my books through three systems: Dewey Decimal, Library of Congress, and the Library Company’s own Smith system. For the first two, I used the Library of Congress’s catalog to look up my books and find the call numbers there. For any books not in the catalog, I used charts on these systems to classify the books myself.

I started with the Dewey Decimal System. Created by Melvill Dewey in 1876, this system is used across America in school and public libraries. It uses numbers with decimal points to organize books by subject. There are ten main sections: Computer Science, Information and General works; Philosophy and Psychology; Religion; Social Sciences; Language; Science; Technology; Arts and Recreation; Literature; and History and Geography.

One of the most interesting things about classification systems is that you can see what people consider important based on what they use to classify their books. For example, I clearly have a love for speculative fiction, mysteries, and the theater since I have entire shelves devoted to those subjects. Maybe you might have more books about American history or self-help guides. Looking at systems like Dewey, we can clearly see some of the biases inherent in this system. For example, Language books are shelved in the 400 section. Under this section, there are subsections for English, German, French, Italian, Spanish and Portuguese, Latin, Greek, and Other languages. Only European languages have their own subsections, revealing the Eurocentric bias this system was based on. This same bias is present in the section on Literature (800s). The Religion section (200s) has 7 subsections devoted to Christianity and only 1 for “Other Religions.” Looking at this system, I can clearly see what were considered important subjects to its creator. But how do my own books fit into this system?

Most of the books I own are fiction, so almost all of them were sorted into the 800s. One thing I liked was that I was able to sort my more general “literature” books into groups based on when they were written. I also liked that some of the sections I had created stayed intact: cookbooks, mystery novels, and plays for example. I did not like that my giant books on astronomy now dominate the top shelf. I have a lot of literature books in fancy bindings that I like to keep together as a set. Now they are shelved all over the bookcase instead! This system also separated my art books because they all dealt with different mediums. Overall, for the size of my collection, I don’t think this was useful. I don’t have enough books of different kinds to make this system worth it.

Three of my art books shelved apart from each other

Next I tried out the Library of Congress Classification System. Created in 1904, this system is used by university and college libraries and other libraries geared toward research. It uses a combination of letters and numbers to organize books. One bias that jumps out at me immediately is that there are two sections devoted to American history (E and F) and only one for general world history (D). This is not really surprising since this system was developed for American libraries. Another bias that stood out was the HQ subsection. All Social Sciences are shelved under “H” and the “Q” subsection denotes the family, marriage, and women. The fact that books on women’s history and achievements are shelved with books on family management shows the bias of where women were thought to belong when this system was created. Let’s see how my books fit into this system.

I actually like the first shelf in this system! It includes all of my art and theory books in one spot, keeps my queer books together, and puts them all in an understandable order. I was upset to see that some of my plays got separated. Literature is organized by the year of publication so my Oscar Wilde and Tom Stoppard are far away from my Shakespeare. Some of my Agatha Christie books got classified as literature and some as fiction, so they too were separated. The cookbooks, which in Dewey were on shelf 1, have relocated in basically the same order to shelf 5. While I liked this system a lot better than Dewey, it still has some bugs to work out.

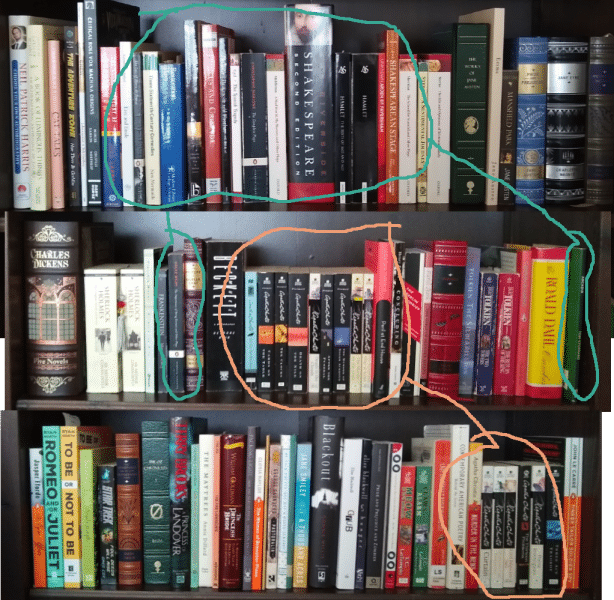

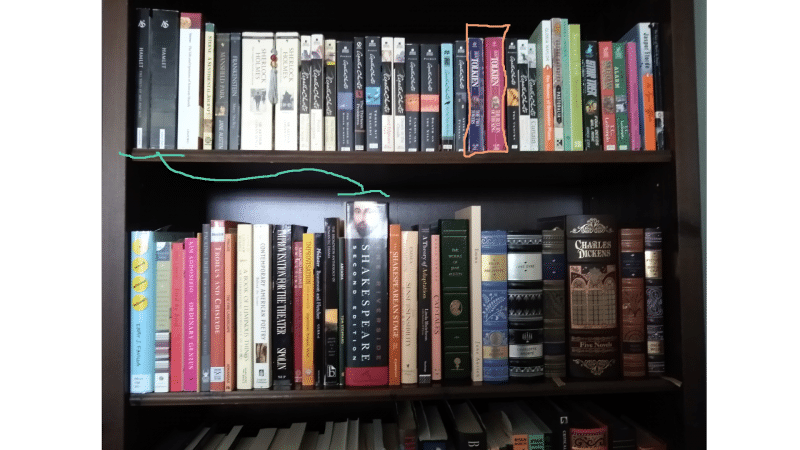

The plays, circled in blue, are separated by date of publication. The Agatha Christies, circled in orange, are separated by whether they were classified as “literature” or “fiction.”

The final system I wanted to try out is the unique system that I work with every day at the Library Company. Created by librarian Lloyd P. Smith, this system uses letters and numbers to classify books. It uses vowels as the main sections, which are: Religion, Jurisprudence, Sciences and Arts, Belles Lettres, History, and Bibliography. Unlike the previous two systems that try to assign very granular call numbers to each book, the Smith system only gives general categories and then books are shelved in order in which they are received by the library. This generally means that older books will be shelved first and more recently published books will be shelved last. Since I can’t remember when I got most of my books I will shelve them by publication date. We also shelve our books separately based on their sizes, so within each section I will shelve small, medium, and large books separately. Let’s see how this looks.

Even before shelving the books, I ran into problems. This system was created between 1878 and 1882, so some of my books don’t fit into its categories. For example, I have some narrative comic books; are they literature or art? I chose to classify them as literature since their main purpose is to tell a story. Previous librarians have added in a subsection under drama for motion pictures. Is this where my art books should live? Is the art book on the making of Paranorman, a stop-motion animation film, a book about motion pictures or sculpture art? I chose to class my art books under the medium they discuss rather than putting them all under motion pictures.

On the positives: my plays are all back together! Although, my Hamlets are separated from my complete works of Shakespeare due to their size differences. My Agatha Christies have the same problem with the added complication of J.R.R. Tolkien publishing his books in the midst of hers. Overall, this may be my favorite system so far. I like having my literature books in date order. This also keeps poetry and drama in their own separate categories. The top shelf again became the shelf for instructional and non-fiction books. Interesting to note, my Harry Potter books have stayed in the same spot through all of these systems. I am choosing to believe magic was involved somehow.

Hamlets and Shakespeare (blue) separated by size. My Lord of the Rings books (orange) stuck in the middle of the Agatha Christies.

So what has this experience taught me? I’ve decided to go back to a modified SystEm. I like having my books organized in a way that has meaning to me. I will take some ideas from the other systems, such as sorting books by size and date of publication. This will help put my literature books in better order and allow me to keep my oversize art books on the bottom shelf. I want to separate out my speculative fiction and mystery fiction again into their own discrete categories, but I will probably keep the ordering of my other literature books from the LCP system and the ordering of my nonfiction books from the Library of Congress system. While this experiment took me many days to complete, I have a much better grasp on the books in my collection (or at least the ones on this particular shelf).

How are your books organized? Is there a classification system that speaks to you? Would using one of the systems listed above enhance your bookshelves? Or do you feel confident in your own home-spun system? There’s never been a better time to re-examine your bookshelf and do a little experimenting to find what works best for you!

RESOURCES:

The Library of Congress catalog. Most titles here will include both a Library of Congress and a Dewey number: https://catalog.loc.gov/

You can use this website to encode your own books with Dewey numbers by clicking through each section: https://www.librarything.com/mds/0

Overview of the Library of Congress system: https://www.loc.gov/catdir/cpso/lcco/

This book breaks down the original Library Company classification system: https://www.google.com/books/edition/On_the_Classification_of_Books/IvcYAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0