The following post was written by Imperfect History Digital Catalog guest cataloger Tanya Sheehan about her experience. The Catalog creatively engages with the Imperfect History exhibition themes of (un)conscious bias and multiple viewpoints. Four guest catalogers from the curatorial, art history, and studio art fields authored concise descriptions of the same visual material, from their individual perspective as affected by their discipline. A traditionally standardized, “objective” process was made pro-actively subjective and diverse.

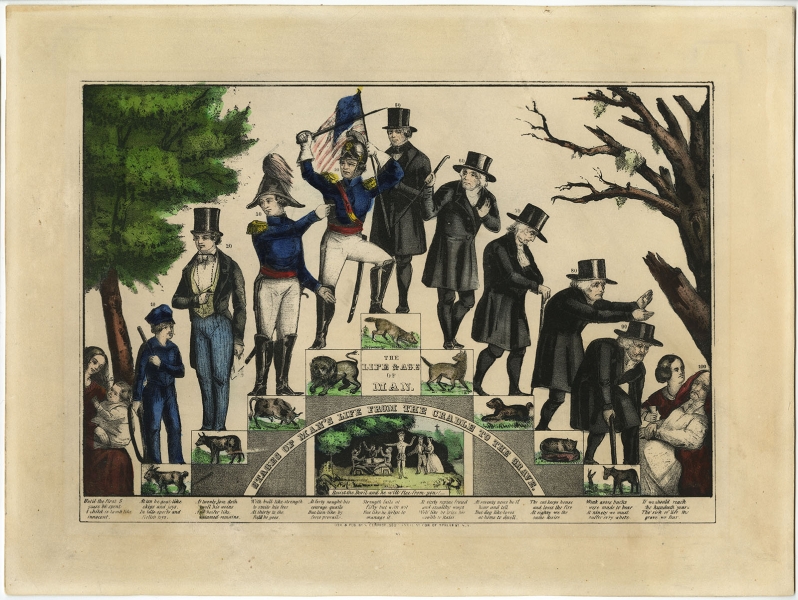

Life & Age of Man. Stages of Man’s Life from the Cradle to the Grave (New York: N. Currier, ca. 1847). Hand-colored lithograph.

Imperfect History

Knowing the goals of Imperfect History—to examine the role that disciplinary perspectives play in interpretations of the Library Company’s graphics collections—made me even more conscious than usual of the reading methods I apply to objects as an art historian. And not just any art historian, but one whose scholarship and teaching have focused on the role that images have played in the construction of social identities. That work has relied on looking closely, asking probing critical questions about primary sources, and reading widely to understand the many contexts in which images communicate meanings to viewers.

The COVID-19 pandemic made close looking in this case more challenging than I had anticipated. Whenever possible, I begin an interpretation by spending time with historical objects in person—holding them in my hands, assessing their size and weight, inspecting them under a magnifying glass, reflecting on their condition—but my inability to travel safely between Maine and Philadelphia required me to work with digital scans. The high resolution of those scans thankfully allowed me to scrutinize the tiniest details on my computer screen. I could also rely on previous experience, including many months conducting research at the Library Company and decades of collecting, studying firsthand, and teaching with objects like those featured in Imperfect History. When it came to looking beyond those objects, however, I had to work exclusively with digitized materials online. I longed to study objects side-by-side at the Library Company and to illustrate other images in my catalogue records, because I understood the print, daguerreotype, and watercolor as acquiring meaning in conversation with other images. In the case of Ages of Man by Currier & Ives, my record invokes comparisons to the companion Ages of Woman as well as artworks depicting the Biblical figures of Adam and Eve, the Virgin Mary, and Jesus Christ. A longer record might have referenced allegorical paintings comparing humans to animals, 17th-century woodcuts accompanying counting verses, and 19th-century prints of men’s fashions.

While I put heavy stock in visual analysis, I have never limited my interpretations to what might be most visible in a picture. In approaching Ages of Man, for example, I was drawn to the details on the margins of the print. This was not merely an impulse to read against the grain; my research on race and representation has trained me to look beyond the privileged center of things and attend to the power structures that keep certain figures silent or unseen. The result was a reading of Ages of Man as saying just as much about women as it did about men and masculinity. In the case of the daguerreotype of the unidentified sitter, a traditionally marginalized figure—an African American woman—takes center stage, and yet so much information remains lost to history, from the subject’s name and life story to the date and occasion of her sitting. Instead of allowing missing facts to thwart an analysis of the object, I relied on my knowledge of the conditions of studio portraiture at the time and African Americans’ engagement with photography as an instrument of empowerment in the 19th century. Would I like to read a diary entry in which the sitter identifies her relationship to the Dickerson family and describes her experience that day in Samuel Broadbent’s studio? Sure. But I would not take that source at face value or use it to foreclose consideration of the daguerreotype in relation to a variety of social and cultural discourses. Every text—visual or otherwise—requires us to remain relentlessly curious about its many meanings.

Tanya Sheehan, William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of Art, Colby College

Imperfect History is supported by the Henry Luce Foundation, Walter J. Miller Trust, Center for American Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Jay Robert Stiefel and Terra Foundation for American Art.