Interpreting 19th Century Documents: A Sample from the James Barton Longacre Collection

Alexis Jimenez, Archival Project Intern

Processing archival collections present many challenges for archivists. One particular complication can be interpreting someone’s handwriting. All too often there are flourishes coupled with such a variety of styles of handwriting that deciphering the information within those documents can become time consuming. In addition, there are abbreviations that were utilized in the 19th century that can be confusing to someone reading these documents in the 21st century.

This is exactly the type of difficulty we face while processing the James Barton Longacre Collection. Longacre was Chief Engraver of the Philadelphia mint from 1844 to 1869. A large part of the collection is comprised of correspondence from various people throughout the course of his life. Given the number of different people who wrote the letters, there are of course an equal amount of contrasting styles of handwriting. One reason for the inconsistencies in the handwriting of the 19th century is the fact that until the 20th century there was more than one style of cursive writing that existed. Furthermore, things like grammar, spelling, and punctuation were still early in standardization. And most obvious, everyone’s writing is unique in some way or another.

A useful tactic to begin interpreting material from the past is to try to read the entire document and even speak it aloud. Often times, there are words that may not be legible initially, but even something as simple as speaking the words will help to give context that allows you to figure out words that are illegible at first glance.

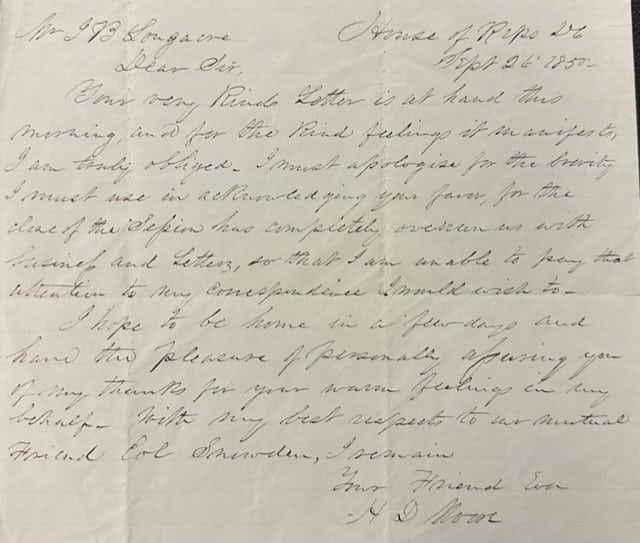

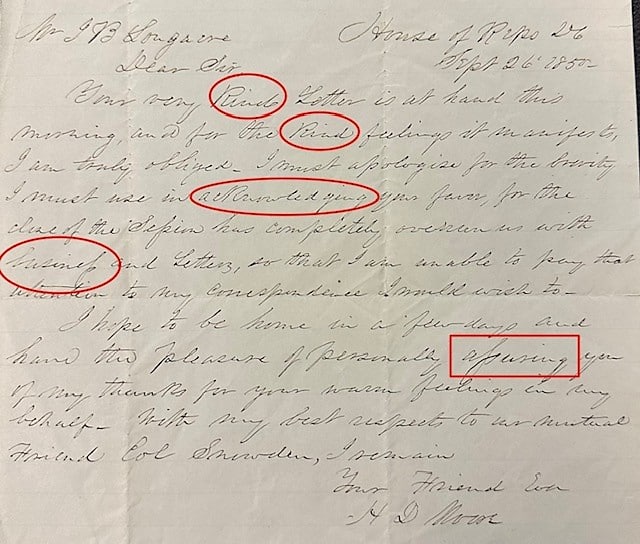

In this example, there are several words that may be difficult to understand at first read through.[1]

In particular, there are words like the ones marked in red in this second image that could potentially be confusing. In the opening sentence circled in red is a word that looks like it could be Rinds; but that wouldn’t make sense in the context of the sentence. That same word also appears again in the first sentence. So what is it?

Well, if you read the sentence and skip the word that seems odd it states, “Your very ____ Letter is at hand this morning, and for the ______ feelings it manifests, I am truly obliged.” If you think of words that it looks like that would make sense then it becomes clearer that it is the word, “kind.” The capital “K” looks like an “R,” but it is clearly just the author’s personal style of writing that is causing the confusion.

The third circled word may have been confusing, but now that we know from the last circled word the author’s “k” tends to look like an “r” it should be easier to see that word is, “acknowledging.”

The next two words that are marked with red are a little trickier than the words we have deciphered so far. The context surrounding the first word of those two isn’t quite as helpful either. It is essential to understand that they used a specific standard when writing words with a double-s during that time period.

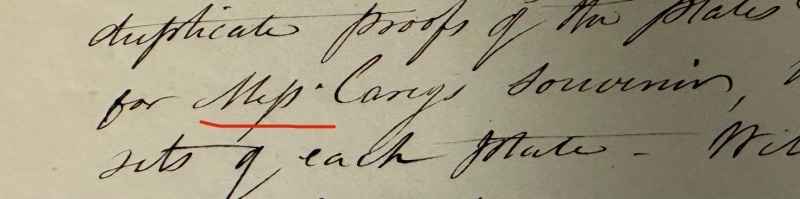

A common convention that can be confusing in 19th century documents are the words that use a double-s “ss” such as in the word, “distress.” Words that use a double-s will often look like “fs” or “ff” when written and can be seen in these two samples taken from the Longacre Collection. The first example is from a letter written by Asher B. Durand to Mr. Longacre in which he talks about plates he made for Miss Carey. As you can see, Miss looks like Mifs.[2]

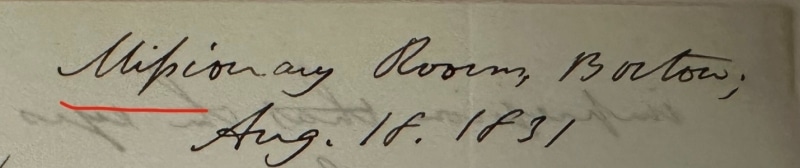

And again we see the “ss” in “Missionary” from this letter from David Greene to Longacre that looks like “Mifsionary.”[3]

Understanding the accepted way of writing in a time period, such as the way double-s words were written can help make identifying words much easier. And in the case of the letter we seek to interpret, we can see that circled word in question is “business.” The other word with the red rectangle is “assuring.”

Now that we have those tricky words figured out, the letter becomes easier to understand and reads as follows-

Your very kind Letter is at hand this morning and for the kind feelings it manifests, I am truly obliged. I must apologise for the brevity I must use in acknowledging your favor, for the size of the Sepia has completely overrun us with business and letters, so that I am unable to pay that attention to my correspondence I would wish to-

I hope to be home in a few days and have the pleasure of personally assuring you of my thanks for your warm feelings in my behalf. With my best respects to our mutual Friend Col Snowden, I remain.

Your Friend Ever

Of course, one last piece of the puzzle remains. Who authored this letter? It is obvious that the two initials are H D, but what could the last name be? The surname could be Morse and in fact, there was an H. D. Morse who was alive during the time period that matches the letter. Henry D. Morse was an artist that very well could have been friends with Longacre. However, the letter from the person in question was sent from the House of Representatives and Morse spent his life in Boston, so this is almost certainly not him. There was a member of the House of Representatives though named Henry Dunning Moore, and he is who wrote this letter.

Figuring out the names of correspondents is another aspect of the documents in the Longacre Collection that can be an obstacle. There are times when a person signed their name using an abbreviation or only their initials. Some common name abbreviations used in this era include:

Eliz. = Elizabeth

Geo. = George

Jas. = James

Jno. = John

Thom. = Thomas

Thos = Thomas

Wm. = William

If the person writing the letter only uses their initials, it really requires detective work to discover who they are. Reading the entire document and using things like the date it was written, where it was sent from, and what the letter is about are all important clues that can help determine the author. Here are a few more example signatures from letters in the Longacre Collection that are somewhat ambiguous and difficult to read.

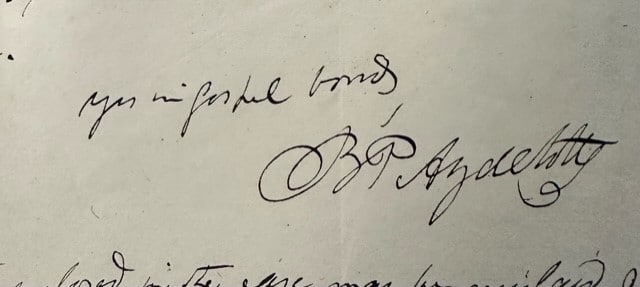

This signature is particularly challenging because the person who it belongs to only used their first and middle initial with their last name. Luckily, the B and P are both clear and easy to read. The last name is a little more questionable. The first letter is definitely an A, but the letter after that could be a z followed by d then e. The subsequent letters could in theory be any combination of letters. Fortunately, the person who wrote the letter included a lot of information that made it easy to identify him. This signature belonged to Benjamin Parham Aydelott, who was the President of Woodward College in Cincinnati.[4]

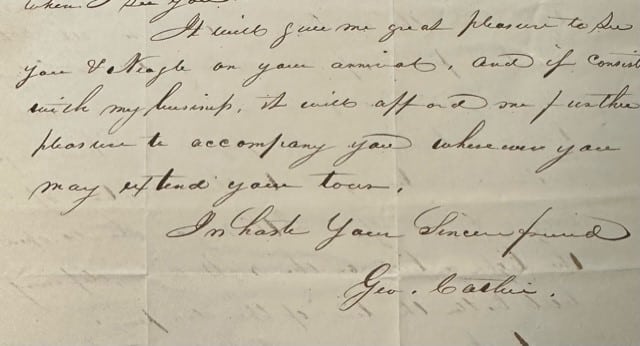

The next signature is a little easier to read. In this example you can see the author abbreviate his first name as Geo. for George. The last name is fairly clear as well, but the handwriting style of the individual does make it slightly harder to read.

The last name is Catlin. George Catlin was an artist, traveler, and author. In the Longacre Collection there are three letters from Catlin and the context of the letters helped to identify that it was indeed him.[5]

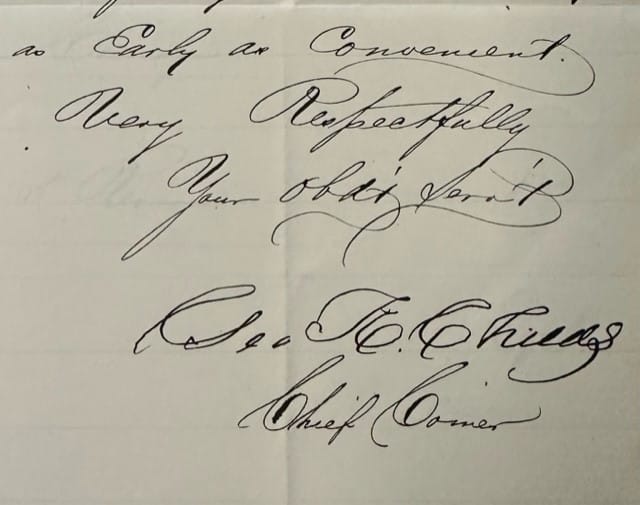

And here is the last instance of a signature that is hard to read due to the flourishes and style of the author.

As you can see, despite the uncertainty in the signature caused by the style of handwriting, the name of the person who penned the letter is easily identified by his official title of Chief Coiner of the United States Mint. This means it would have to be George K. Childs who was the Chief Coiner of the mint when the letter was written in 1856.[6]

After viewing samples of correspondence from the James Barton Longacre Collection you are able to get a glimpse of the work that goes into understanding and processing documents from the 19th century or any older handwritten material. Deciphering these texts requires not only reading skills but also research skills as well as a little bit of detective work. The Longacre Collection is available at the Library Company of Philadelphia for researchers and anyone interested in learning more.

The James Barton Longacre Collection Archival Project was made possible by the generosity of our Sponsor Kurt Brintzenhofe.

[1] Henry Dunning Moore to James Barton Longacre, September 26, 1850. The Library Company of Philadelphia.

[2] Asher B. Durand to James Barton Longacre, September 21, 1827. The Library Company of Philadelphia. 12420.F.77.

[3] David Greene to James Barton Longacre, August 18, 1831. The Library Company of Philadelphia. 12420.F.101.

[4] Benjamin Parham Aydelott to F.N. Porter, April 27, 1837. The Library Company of Philadelphia. 12420.F.9A.

[5] George Catlin to James Barton Longacre, n.d. The Library Company of Philadelphia. 12420.F.24.

[6] George K. Childs to James Barton Longacre, September 30, 1856. The Library Company of Philadelphia. 12420.F.32.