The Library Company‘s Relationship with the Free Black Community in Philadelphia

Dana Dorman, Archivist, Library Company Papers Project

In celebration of Black History Month, I wanted to use this month’s blog post to highlight the Library Company’s relationship with Philadelphia’s free Black community during the 18th and 19th centuries.

Historian Sean D. Moore has pointed out that the Library Company’s early white shareholders had connections to both slavery and abolition, and perhaps not in equal measure. He makes a compelling case that the Library Company’s orientation toward abolitionism showed Philadelphia’s “Enlightened cosmopolitanism,” but may not have been a viewpoint held by the majority of shareholders.[i]

That said, we know that the Library Company’s holdings in these early years certainly included works about Africa and the Atlantic world, about abolitionism and anti-slavery, and eventually works written by Black authors.

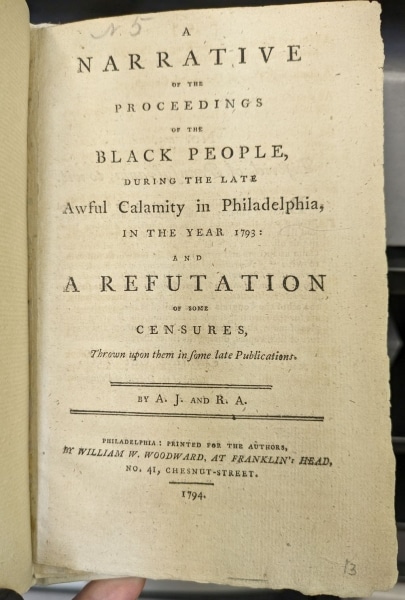

Within a year of its being published in 1794, we had not one but two copies of the pamphlet written by Absalom Jones (1746-1818) and Richard Allen (1760-1831) to lift up the heroic efforts of the Black community during the city’s Yellow Fever epidemic. (Jones and Allen are credited as being the first African American authors to attain a federal copyright for this work.)[ii]

Image: Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, “A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, During the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia, in the Year 1793: And a Refutation of Some Censures, Thrown Upon Them in Some Late Publications.” (Philadelphia: printed by William W. Woodward, 1774).

I have not yet found evidence in our institutional archives that the Library Company either welcomed or turned away the city’s growing Black community as readers and shareholders during these years.

Since the LCP Papers Project focuses on our first 150 years of history – up through 1881 – I can say that our pre-1881 shareholder list includes none of the prominent Black men who had the type of wealth or strong civic connections that typically opened doors to shareholding. I have not found James Forten (1766-1842) or William Whipper (1804-1876); no Robert Douglass, Jr. (1809-1887), William Still (1821-1902), or James Needham (1848-1936).

Instead, a group of Black Philadelphians took the initiative to create their own library and founded the Library Company of Colored People on January 1, 1833.[iii]

By 1841, one observer noted that this other library included “nearly six hundred volumes of valuable historical, scientific and miscellaneous works.” It also sponsored debates to encourage “members to historical and other researches, and for practicing them in the arts of elocution and public speaking.”[iv]

While much more research is needed to understand the history of the Library Company of Colored People, it is known that it lasted until at least 1862 according to newspaper notices, and perhaps even longer.

Meanwhile, back at the Library Company of Philadelphia, the best record of the Black community’s contributions to the organization’s growth by 1881 is in our hiring of specific laborers or tradespeople over the years.

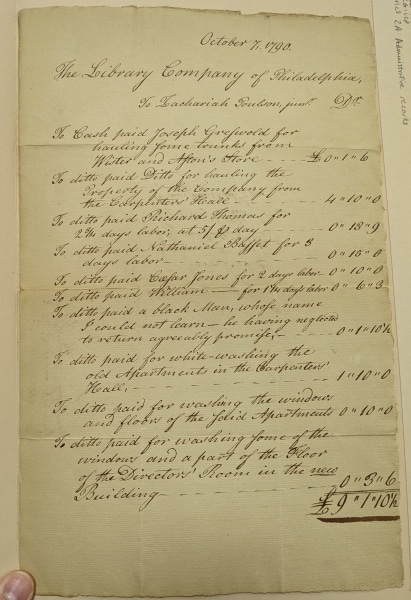

For instance, when librarian Zachariah Poulson, Jr. listed out his cash expenses in October 1790 as he oversaw the library’s move from the second floor of Carpenter’s Hall to our new building at 5th and Library Streets, he listed one of his helpers as “a black man whose name I could not learn – he having neglected to return agreeably [as] promise[d].” Perhaps other men on Poulson’s list of helpers were also Black?

Image: Account of Zachariah Poulson, Jr. for moving books to the new building, October 7, 1790. LCP Records (MSS00270).

Later, our financial records include invoices and receipts from African American restauranteurs and caterers like James Prosser and the P. Albert Dutreuille Company. Prosser supplied 12 terrapins and 600 oysters for a Library Company dinner in 1822, and we have his invoices for dozens of Library Company dinners held during the 1840s.

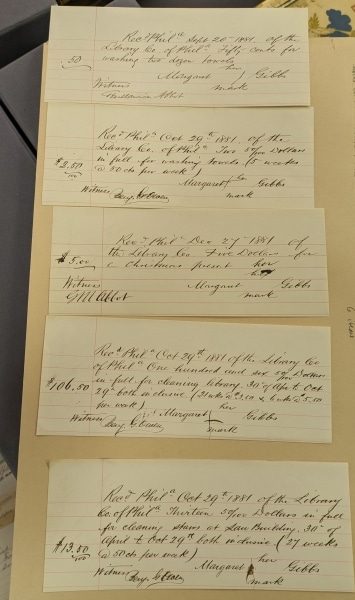

Even later, African American Margaret Gibbs was a “scrubber” for the Library Company for roughly 30 years between the 1850s and the 1880s. Surviving receipts show that the Library Company paid her for cleaning the Library Company, cleaning the stairs at the Law Building (owned by the Library Company), washing towels, and even cooking and serving as waitress at a Library Company annual meeting. In December 1881, she also received $5 as “a Christmas present.”[v]

Image: Margaret Gibbs receipts, 1881. LCP Records (MSS00270).

These receipts and thousands of other early Library Company records are being digitized as part of the LCP Papers Project, and will soon be available online.

As we continue to make our institutional archives more accessible, we are hopeful that scholars may be able to identify more ties between the Library Company and the free Black community in Philadelphia during our early years.

In the meantime, you can learn more about the city’s early Black community by browsing through some of the Library Company’s past digital exhibitions, including Black Founders: The Free Black Community in the Early Republic and From Negro Pasts to Afro-Futures: Black Creative Re-imaginings.

Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this blog post do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

[i] For instance, see page 180 in Sean D. Moore, Slavery and the Making of Early American Libraries: British Literature, Political Thought, and the Transatlantic Book Trade 1731-1814 (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2019).

[ii] For much more about the Absalom Jones’ and Richard Allen’s “Narrative,” see Richard S. Newman, Freedom’s Prophet: Bishop Richard Allen, the AME Church, and the Black Founding Fathers (New York: New York University Press, 2008) and Richard Newman, Patrick Rael, Philip Lapsansky, eds., Pamphlets of Protest: An Anthology of Early African-American Protest Literature, 1790-1860 (New York and London: Routledge, 2001).

[iii] Joseph Willson, Sketches of the Higher Classes of Colored Society in Philadelphia by a Southerner (Philadelphia: Merrihew and Thompson, printers, 1841). For more about Black literary societies, see Elizabeth McHenry, Forgotten Readers: Recovering the Lost History of African American Literary Societies (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002).

[iv] Willson, pages 98-99.

[v] Librarian George M. Abbot mentioned Margaret Gibbs at least twice in his history of the Library Company. When he joined staff in 1863, Abbot says he was one of three staff: “Mr. [Lloyd P.] Smith, myself, and an old colored woman, Margaret Gibbs, the latter attending to the cleaning” (p. 21). He also mentions Gibbs on page 22, saying she believed that a ghost wandered the galleries and once struck her niece “who was helping her” with a cane. George Maurice Abbot, A Short History of the Library Company of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: Library Company of Philadelphia, 1913).