What does it mean to Redraw History?

Needs a Caption

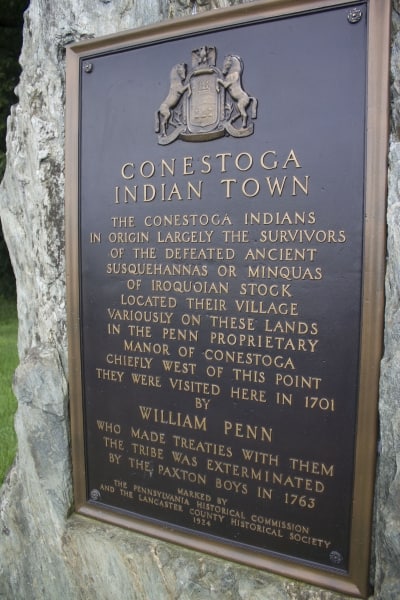

In December 1763, a mob of settlers from Paxtang Township murdered 20 unarmed Susquehannock Indians in Lancaster County. A month later, hundreds of “Paxton Boys” marched toward Philadelphia to menace and possibly kill more refugee Indians who sought the protection of the Pennsylvania government. While Benjamin Franklin halted the march just outside of Philadelphia in Germantown, supporters of the Paxton Boys and their critics spent the next year battling in print through a pamphlet war that was not so different from the Twitter wars of today.

For historians, the Paxton massacre(s) and ensuing pamphlet war are well-trodden territory. In 2013, Daniel Richter (McNeil Center for Early American Studies) organized a 250th anniversary conference, from which Patrick Spero (American Philosophical Society) edited a special issue of Early American Studies in 2016. And, of course, the de facto edition to the ensuing pamphlet war, John Raine Dunbar’s The Paxton Papers (1957) recently marked its 60th anniversary.

However, as I began to build my own digital collection and scholarly edition to that pamphlet war (Digital Paxton), I was struck by how much of that debate unfolded outside of pamphlets. Alongside a wealth of other printed materials—newsprint, books, broadsides, and political cartoons—I discovered dozens of diaries, letters, and treaty minutes that not only placed the massacre in a longer debate about colonial settlement, democratic representation, and racial identification, but also unsettled the singular authority of those colonial records. For example, the political cartoon “Franklin and the Quakers” doesn’t make a lot of sense without some understanding of Quaker-Indian diplomacy (via the Friendly Association) during the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763). Furthermore, the more I dug into those diplomatic records, the more I reckoned with the difficulty of discerning voices of Delaware, Lenni Lenape, or Susquehannock (Conestoga) that were not excerpted or mediated through their colonial trading partners.

In the case of Digital Paxton, I’ve tried to surface those absences by placing colonial and indigenous records in the same repository (digital collection), signposting archival gaps through contextual essays, such as Darvin Martin’s “History of Conestoga Indiantown.” But what if we could imagine a perspective on the Paxton massacre that, given the genocide of the Susquehannock, could not be retrieved? That is, what if, instead of telling a story about the Paxton vigilantes, we sought to tell a story about the Conestoga, their resilience, and their formative role in the history of the colony of Pennsylvania?

Redrawing History: Indigenous Perspectives on Colonial America takes up that challenge. Supported by a major grant to the Library Company of Philadelphia by The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, this project features three key components: an educational graphic novel, a national educators’ seminar, and an exhibition, accompanied by a series of public programs.

The graphic novel is central to this project because it will empower indigenous creative partners to explore, question, and reinterpret—or “redraw”—historical records accessible through Digital Paxton. In addition to an advisory board comprised of subject area specialists from the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, Free Library of Philadelphia, and University of Pennsylvania (including, notably, Daniel Richter, who organized of the 250th anniversary conference), the project also includes leadership from the Delaware Tribe and local indigenous communities at the Circle Legacy Center.

Notably, the graphic novel will be written, illustrated, and published by Native American artists: Dr. Lee Francis (Laguna Pueblo) will write the script; Weshoyot Alvitre (Tongva) will pencil, ink, and color pages; and Native Realities Press will publish the graphic novel with free distribution to all 573 federally-recognized tribes. As Creative Director of the project, I’m a sort of air traffic controller: I’ll queue up scholars, scholarship, and historical records, make new primary and secondary source materials freely accessible on Digital Paxton, and seek new opportunities to connect our book with the broader public. This requires a great deal of restraint from an academic, where working alone is all too common, but I’m thrilled to see what emerges from this scholarly-creative collaboration. The book will be available in fall of 2019, with free accessibility online.

Meanwhile, in the summer of 2019, the Library Company of Philadelphia will partner with the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History to host a national educators’ institute. We’ll produce a teaching curriculum, keyed to common core standards, so that middle school and high school teachers at public schools have everything they need to bring our graphic novel—and the Paxton incident—into their classrooms. The curricula will be folded into the back of the graphic novel and made freely accessible online.

Finally, between the fall of 2019 and spring of 2020, I will curate an exhibition of the artwork that Alvitre creates for the graphic novel juxtaposed against the diverse historical records available at the Library Company of Philadelphia. Alongside that exhibition, we will offer a host of programs through which the public may discover the project and meet our artists and advisory board. As with the book and educational curricula, the Library Company exhibition will be free and open to public.

We’re just at the beginning of this process and more details will come into focus in the coming months. I encourage you to return to this site for all of the latest updates.

I, for one, feel humbled to play some small role in this extraordinary project. Thank you for taking the time to read this post, and thank you especially to the Library Company of Philadelphia and The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage for supporting this innovative approach to public art and humanities.

Redrawing History: Indigenous Perspectives on Colonial America has been supported by The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage.