Digital Paxton: An Origin Story

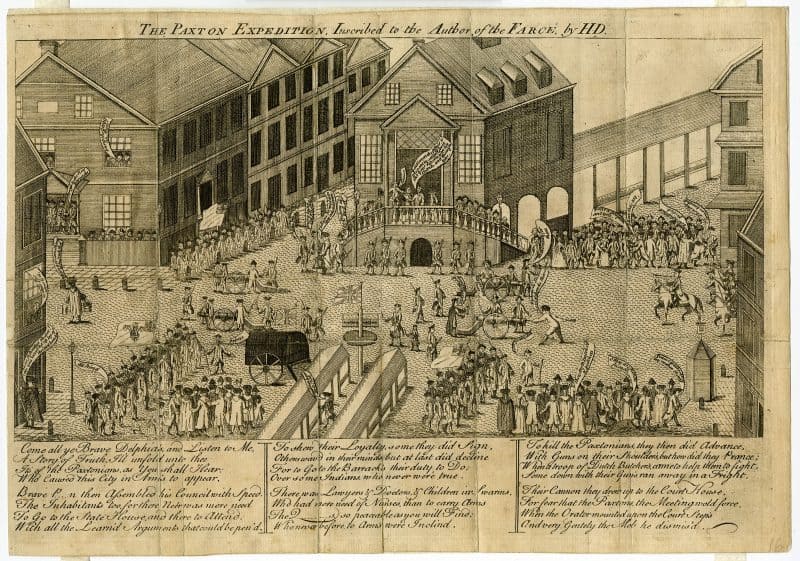

Dawkins, Henry. The Paxton Expedition: Inscribed to the Author of the Farce (Philadelphia: 1764).

I discovered the 1764 Paxton pamphlet war by way of the 60-year-old edition that graces just about every bibliography: John Raine Dunbar’s The Paxton Papers (1957). I approached the Paxton massacre as neither an historian nor a Philadelphian. (I had studied early American literature in New York.)

However, as Edward White, James Myers, and Scott Gordon have demonstrated, these records present a bounty for literary scholars eager to explore their diverse forms and idiosyncratic rhetorical techniques. Researchers will discover dialogues and epitaphs, poems and songs, satires and farces flourished with evocations of “White Christian Savages,” troops of “Dutch Butchers,” and Quakers “thirsting for the Blood” of opponents.

Furthermore, as I dug deeper into the rich Paxton materials available at the Library Company of Philadelphia, I came to appreciate how much of the incident isn’t accessible in Dunbar’s edition and cannot be evaluated within the narrow frame of the pamphlet war.

To be fair, Dunbar was bound by the form of his edition. Tallying 400 pages, The Paxton Papers is a significant—and substantive—scholarly edition. But what if one wasn’t bound by the constraints of print? What else might we choose to include in twenty-first century Paxton Papers?

Digital Paxton begins to answer that question, and, in the process, it both unsettles the conventions of a scholarly edition and blurs the boundaries between an edition, a collection, and a teaching tool.

I began work on Digital Paxton in the spring of 2016. While this project was my idea, it simply would not be a reality without the records, expertise, and institutional investments of my founding partners, the Library Company of Philadelphia and the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. I traveled to Philadelphia as a grad student with a wild idea. Both institutions took a chance and invested in it.

Thanks to a modest travel grant from my university (Fordham University), I shuttled between New York and Philadelphia half a dozen times that spring to participate in planning.

Over the first half of 2016, I created design mockups so that we could test different approaches for presenting and structuring data, drafted memoranda of understanding to delimit roles, responsibilities, and sustainability plans, and worked closely with Librarian Jim Green to identify the most suitable pamphlets, broadsides, political cartoons, and manuscripts available at both institutions. Samantha Miller from the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and Nicole Joniec from the Library Company helped me to develop a set of inter-institutional standards for scanning, naming conventions, and rights to long-term digital storage. Perhaps most importantly, each institution funded a summer intern who scanned and transcribed items for Digital Paxton. Before Grace Tang and Hunter Johnson began their assignments in late-June, I worked with Nicole Scalessa from the Library Company to draft a work plan, a spreadsheet through which we could track progress, and a document to which we could add full-text transcriptions.

That first batch of material—1,152 pages in sum—represents nearly one-half of all material available in Digital Paxton. About half of that original corpus was transcribed and fully-searchable, with all images were made publicly available as print-quality 300-dpi JPEGs. Under the Creative Commons 4.0 license, any researcher, student, teacher, or inquisitive visitor can download, use, or reuse images as they wish.

Over the past two years, the project has expanded remarkably as a digital collection. Digital Paxton features almost 2,500 pages as of material, which now includes diaries and letters from LancasterHistory.org and the Moravian Archives of Bethlehem; never-before digitized manuscripts from the American Philosophical Society; treaty minutes from Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections and Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts; and newsprint from the American Antiquarian Society. The project is proud to host contributions from more than a dozen archives, libraries, and cultural institutions, with more than one-third of the digital collection fully-transcribed and searchable (88 records as of September 2018).

Perhaps most importantly, the project has blossomed as a scholarly edition. While Digital Paxton, like Dunbar’s Paxton Papers, features an editor’s introduction, the definitiveness of my framework is complicated by ten additional historical overviews and conceptual keyword essays. For example, Darvin Martin explores the “History of Conestoga Indiantown,” whereas Scott Paul Gordon teases out the complexities of the oft-repeated charge against “Elites.”

The project’s interpretative apparatus is self-consciously interdisciplinary: essays explore the historical bases and literary and material cultures of the Paxton massacre and pamphlet war. Essays are also admirably succinct, written and edited to serve as on-ramps to the project’s digital collection. That is, Digital Paxton interweaves text and context so that visitors can pursue their interests, wherever those curiosities might lead.

Digital Paxton is perhaps most embryonic as a teaching platform. The project hosts several assignments that encourage students to delve into the history of European colonization, to inhabit perspectives of the Paxton allies and their opponents, and to practice paleography through transcription. While those lessons are tailored to higher education, we have some exciting plans to translate the project for middle and high school classrooms. Certainly the graphic novel that we publish via Redrawing History: Indigenous Perspectives on Colonial America will be central to that process. However, the graphic novel is just one leg in an (expanding) educational base.

I hope that interested readers will return to this site to track Digital Paxton’s maturation as a teaching tool, a digital collection, and a scholarly edition.

Redrawing History: Indigenous Perspectives on Colonial America has been supported by The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage.