Searching Through the Catalog: From Print to Cards to Digital

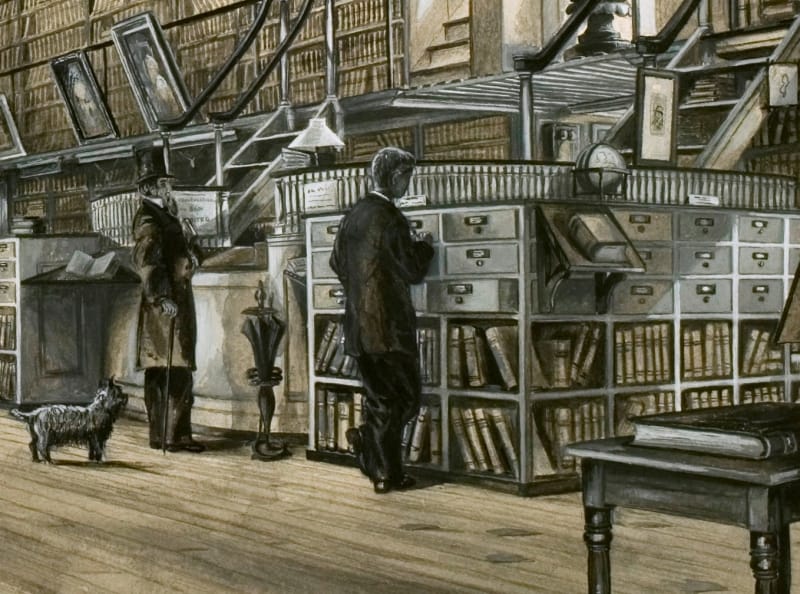

The Library Company of Philadelphia has witnessed numerous changes since its founding in 1731. New technology caused many transformative developments, one of which was the advent of a card catalog. It even altered the physical space, adding a large piece of furniture that became central. A watercolor of the interior of the Library Company’s Fifth Street building by Colin Campbell Cooper shows a patron using a card catalog at the right.

Detail

Colin Campbell Cooper Jr., View of the Interior of Library Hall on Fifth Street (Philadelphia, 1879).

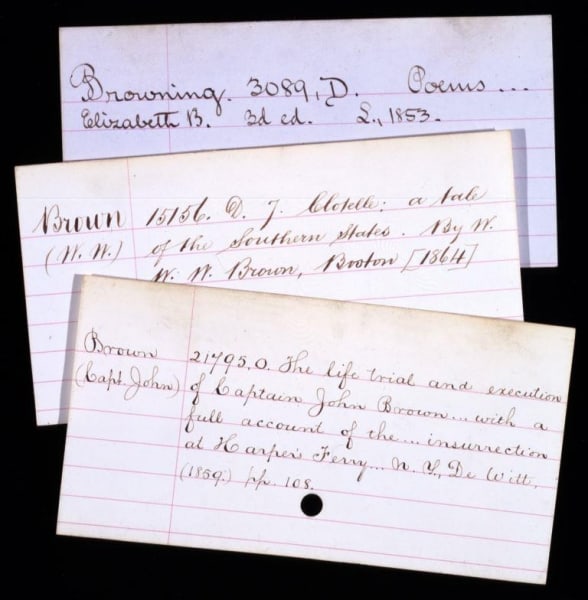

The introduction of the card catalog changed the way librarians organized books and readers found titles. Previously, the Library Company published catalogs listing all of the books in the collection. The first was published in 1741 and the last in 1856. In 1876, the Library’s directors examined the costs of publishing another volume and found it to be prohibitive at $7,000. A card catalog “accessible to all members and readers of the Library” seemed the best solution. They realized that a published catalog is immediately outdated once a new book enters the collection. “The great advantage of such a Catalogue, it is obvious, is that it is never behind hand, but shows at all times the entire acquisition of books from the date of the commencement of the catalogue.”[1] The new card catalog was completed in September 1876 after staff hand wrote 69,460 cards representing all the additions since1856. “The entire cost was $1,087.49 including cases and drawers for the reception of the cards and a stock of some 35,000 cards for future use.”[2] Many libraries no longer have physical card catalogs, a previous ubiquitous stable for reference, but the Library Company still has several, including the one with hand-written cards.

Handwritten cards from the original card catalog, 1876.

These changes happened under Lloyd Pearsall Smith (1822-1886), our librarian from 1851 to 1886 and a founding member of the American Association of Libraries (A.L.A.). As the son of Library Company librarian John Jay Smith (1798-1881), he knew the Library well. He viewed librarianship as a career and through the A.L.A. helped professionalize many aspects of the field.

James Reid Lambdin, Lloyd Pearsall Smith (Philadelphia, ca. 1870s).

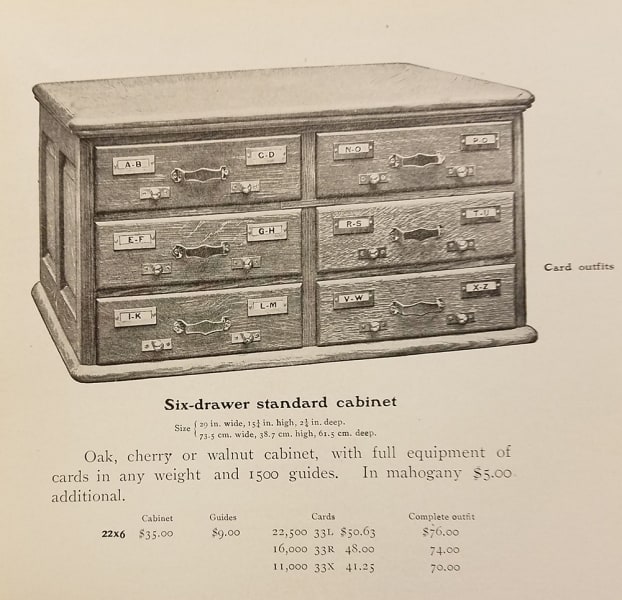

A proponent of the card catalog, the A.L.A. helped standardize the system, including the card sizes, the cabinets, and other tools necessary to make searching easy and universal. Melvil Dewey (1851-1931), most known for his Dewey Decimal Classification, founded the Library Bureau, a business that provided libraries with supplies ranging from furniture to book carts. The Library Company’s Directors’ Minutes show that we purchased material from the Library Bureau, including inkstands and a catalog cabinet.[3]

Library Bureau. Library Catalog: A Descriptive List with Prices (Boston, 1902).

Most libraries used the Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC) System before the Library of Congress (LCC) System to organize their collection of books. Dewey first published his work in 1876. But a number of different librarians created ways of organizing books, including the Library Company’s librarians George Campbell (1783- 1855) and Lloyd P. Smith. The Library’s 1835 published catalog organized the books into five classifications: Bibliography, Religion, Jurisprudence, Sciences and Arts, and Belles Lettres. The 1856 published catalog continued that system adding another category, History. Smith’s classification built on the published catalogs and expanded it to make letters and numbers correspond to the categories. A, E, I, O, U, Y with subcategories labeled as a, b, c, d, etc. and further as 1, 2, 3, etc. For example, a book on the American Revolution would be Uy1 or U for History, y for History about America, and 1 for the Revolution. Smith was aware of Dewey and other librarians who developed new classifications. He even referenced Fred B. Perkin’s 1881 publication A Rational Classification of Literature for Shelving and Cataloguing Books in a Library for having a wonderful index that helped him. Our copy shows his handwritten notes of subjects and their corresponding classification letters. His rationale for not adopting Dewey’s decimal system was that it would be too labor intensive to re-classify the books already in the published catalogs. We continue using the Smith system for the exact same reason. The moving of books into the Library Company’s newly built Ridgway Building on South Broad Street in 1878 afforded the opportunity for them to be “arranged on the shelves—for the first time—according to subjects.”[4] Until then, the books had always been shelved by size (folio, quarto, octavo, or duodecimo) and then by accession number. With the Library Company maintaining two buildings, the Juniper Street building in addition to the Ridgway Building, another new piece of technology aided in staying connected: the telephone. It enabled members to use either branch. An entry ledger was kept at the Juniper Street building, and a librarian at Ridgway would telephone to process the checking in or out of books.

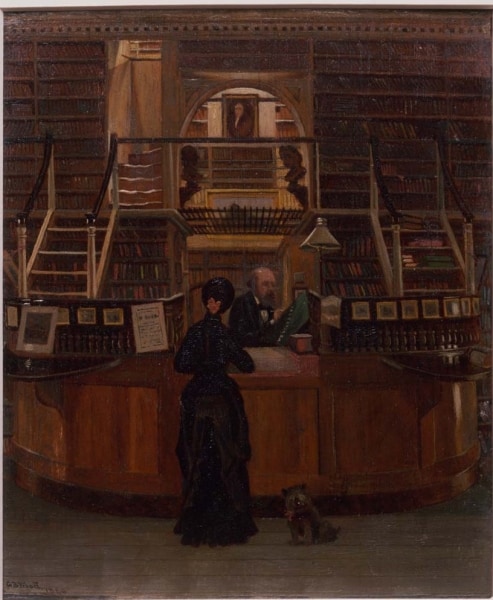

George Bacon Wood, Library Building on Fifth Street (Philadelphia, 1880). Lloyd Smith is behind the circulation desk attending to Library Company Shareholder Anne Hampton Brewster.

A digital catalog now allows people in any location access to search through our book and graphic material and can provide more information than ever could fit onto a card. It includes over 45,000 images and grows every day. But the old card catalog still stands ready for nimble fingers in the Library’s first floor reading room. In a world of rapid change, the library as a bridge to past and future technologies is a comforting place to many.

Linda August, Curator of Art & Artifacts and Visual Materials Cataloger