Seeing Double

As I continue to work with my colleagues in the Graphic Arts Department on the Imperfect History project, I have been spending much of my time considering how our contemporary perspectives can glean new, more inclusive stories from centuries-old objects in our collection. I was therefore eager to come across a stereograph by John Fillis Jarvis which speaks directly to these aims.

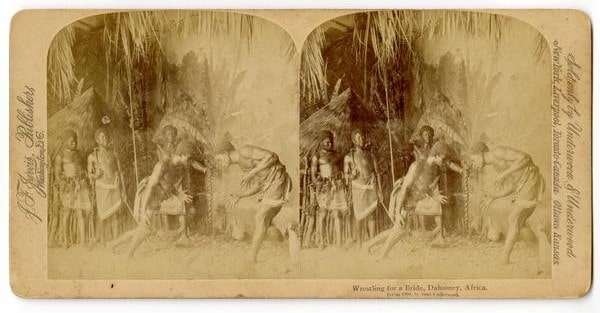

The object in question depicts a group of five Black men dressed in sarongs. Two of the men are engaged in a wrestling match. The caption on the stereograph reads, “Wrestling for a Bride, Dahomey, Africa.” Behind the men is an elaborately decorated set complete with a straw hut, grass, palm trees, and a painted backdrop, each of which is meant to emphasize the exotic locale. Audiences at the time would have looked at the images through a stereoscope, which was meant to create the illusion of three-dimensionality.

John Fillis Jarvis, Wrestling for a Bride, Dahomey Africa (Washington, D.C.: J. F. Jarvis, ca. 1894). Albumen on card mount (stereograph format). Gift of John Serembus.

The Kingdom of Dahomey captured Western imagination during the three hundred year period of its existence before French annexation. In addition to being known for its brigades of female soldiers, the Kingdom was infamous for its warring with neighboring groups and its role in fueling the transatlantic slave trade with captives from its conquests.

Because of its approximate publication date, it’s likely that the stereograph was taken at the World’s Fair in Chicago which took place in 1893. Also known as the Columbian Exposition, this event was held to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the Americas. Forty-six countries from all over the world convened to showcase their achievements, including the Kingdom of Dahomey.

Marriott Canby Morris, Midway Plaisance-Dahomans, 1893. Lantern slide.

The exhibition organizer’s choice to showcase the Dahomey Kingdom and other Black nations, like Haiti and Liberia, prompted protests from African Americans whose experiences and achievements were being omitted from the fair in the United States’ pavilions. This deliberate choice to focus on the more “exotic” cultures reinforced stereotypes about Black people’s “otherness.”

This reinforcement is reflective of the era’s race relations. In the decades leading up to the turn of the century, the promises and progress of the Reconstruction Era had been undone. The subsequent proliferation of racial discrimination and terror ensured that African Americans maintained their status as second-class citizens.

Visual culture played an integral role in maintaining America’s racial order. By depicting Black people as “savages” or “backwards,” objects like this stereograph propped up white supremacist beliefs which were in turn enforced through Jim Crow laws and the onslaught of violence committed by the Ku Klux Klan.

By considering the historical context in which Jarvis’s stereograph was produced, we can see how a photograph meant to entertain and enthrall its audiences can also be a vehicle for maintaining racial inequality in American society.

Kinaya Hassane

Curatorial Fellow, Graphic Arts

Imperfect History is supported by the Henry Luce Foundation, Walter J. Miller Trust, Center for American Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Jay Robert Stiefel and Terra Foundation for American Art.