The following post was written by Kinaya Hassane during her fellowship between October 2019 and May 2021. The William Moses silhouette and cabinet card photograph of an unidentified African American man are included in the Imperfect History exhibition on display until April 8, 2021.

Uncovering Hidden Narratives in American Art

Kinaya Hassane, Former Curatorial Fellow, Graphic Arts

The discipline of art history tends to make a strong distinction between “high” art (typically defined as painting) and “low” art (which encompasses other more accessible and mass produced mediums such as photography and printmaking). This traditional demarcation has meant that most of the canonical works of American art studied by scholars were created by white men from upper class backgrounds. Many of the works in the Graphic Arts Collection, usually conceived of as popular art, prompt us to think expansively about who has contributed to the visual history of the United States. The works implore us to consider the ways that an individual’s race, gender, and class shut them out from traditional forms of art making.

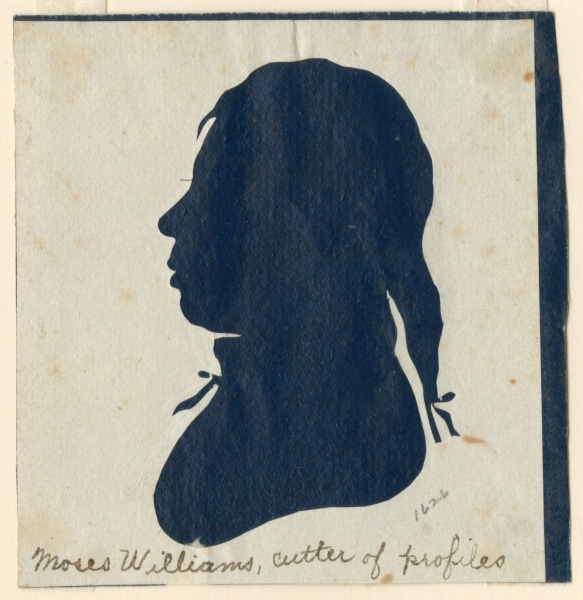

The Peale family of Philadelphia looms large over the history of art in the United States. Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827), the family’s patriarch, became well-known for his painted portraits of the Founding Fathers and established one of the nation’s first museums. Two of his sons, Raphaelle (1774-1825) and Rembrandt (1778-1860), also became well-known painters. A frequently overlooked aspect of the family’s history, however, is the story of Moses Williams (1777-ca. 1825), who was enslaved by the Peales as a young boy and of whom the Library holds a silhouette likeness. Like the Peale siblings, Williams was trained in practical skills to work at the elder Peale’s museum, and he went on to become a talented silhouettist, thus making him among the first professional African American artists. In a 2005 article, art historian Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw argued that it was important to consider the silhouette (which was previously attributed to Raphaelle Peale) as a self-portrait, especially since it is likely that Williams was not taught, like the Peale children, how to paint. Silhouette-making was therefore the one medium through which he could be manumitted, make a living, and assert his newfound freedom. Though this art form did not command the same respect as painting, Williams’s achievements are nonetheless a significant milestone in the larger story of American art.

Moses Williams (or Raphaelle Peale), “Moses Williams, Cutter of Profiles,” ca. 1803. Silhouette.

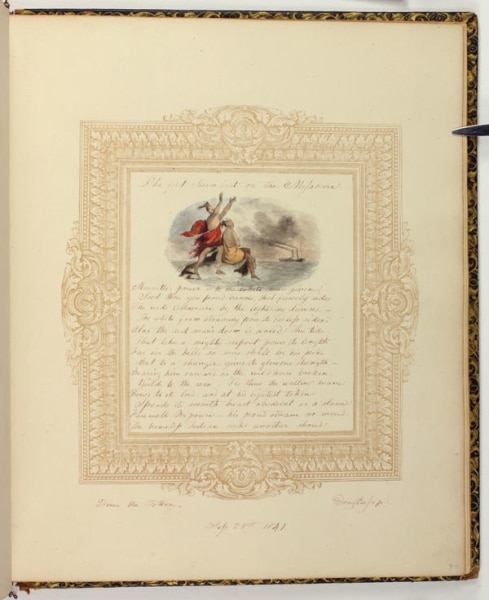

Friendship albums are another medium of American visual culture that continue to offer new perspectives on the study of art. These quotidian objects became popular in the U.S. in the early 19th century, particularly among young women. The Graphic Arts Collection holds rare examples of albums created by three African American women: Amy Matilda Cassey (1808-1856), Martina Dickerson (b. 1829), and Mary Anne Dickerson (1822-1858). All of the young women were members of middle-class Philadelphia families and their albums feature original and transcribed poems on femininity, friendship, and love, giving insight into their lives. Many of these poems are accompanied by beautifully rendered watercolors of various types of flowers. Amy Matilda Cassey’s album also contains a trove of manuscript contributions that detail her involvement in women’s abolitionist groups and friendships with prominent anti-slavery figures, such as Frederick Douglass (1818-1895) and William Lloyd Garrison (1805-1879). Watercolor entries by artist and abolitionist Robert Douglass (1809-1887) and his sister, artist and educator Sarah Mapps Douglass (1806-1882) represent some of the only extant works by these artists, once again illuminating the importance of looking in somewhat non-traditional sources of visual material to tell a more complete history of art in the United States.

Page from album belonging to Martina Dickinson featuring a watercolor by Robert Douglass. 1840-1846. Ink, gouache, watercolor, and graphite.

Photography was another means through which marginalized people could express their identities, especially because of its widespread accessibility. In a portrait of an unidentified African American man, it is clear that the original image of the man was cut and pasted onto a more ornate background. Without any information on where it was taken or who the photographer was, we can only speculate about the circumstances surrounding the image’s creation. It’s possible that the photographer, like the sitter, was Black. They may not have had access to the materials necessary to have a refined and aesthetically pleasing backdrop. They instead used collaging as a creative workaround, perhaps at the behest of their client. Given the likelihood that this photograph was taken in 1875, just before the end of the Reconstruction era, this effort to give the image a heightened air of respectability and individuality reflects the hopes and aspirations of African Americans who were experiencing a short-lived ascent into political power and economic independence. To some, this portrait may be a far cry from the elegant landscape and portrait paintings that came to define American art. However, like many other objects in the Graphic Arts Collection deserving of a critical eye, the photograph exemplifies the innovative artistry that undergirds the evolution of art, “low” and “high,” vernacular and fine, in the United States.

[Unidentified African American Man], ca. 1875. Albumen mounted on cardboard.

Imperfect History is supported by the Henry Luce Foundation, Walter J. Miller Trust, Center for American Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Jay Robert Stiefel and Terra Foundation for American Art.

![[Unidentified African American Man], ca. 1875. Albumen mounted on cardboard. [Unidentified African American Man], ca. 1875. Albumen mounted on cardboard.](https://librarycompany.org/wp-content/uploads/JPG_digitool_127335_Unidentifed-African-American-man-480x600.jpg)