Learning More About Our Shareholders Through the Library Company Papers Project

Dana Dorman, Archivist, Library Company Papers Project

An earlier version of this post appeared in the fall/winter 2023 issue of Occasional Miscellany, a newsletter for members and friends of the Library Company of Philadelphia.

As I continue my archival processing work for the Library Company Papers Project, I am finding that almost all of the records that I’m reviewing have direct or indirect ties to our shareholders. After all, shareholders have been the backbone of the Library Company of Philadelphia since our founding in 1731, and continue to provide crucial support even today.

Our very first shareholder was Robert Grace (d. 1766), who acquired share #1 on November 10, 1731. Grace was a wealthy ironmaster and furnace owner, and in addition to owning share #1, he also was the first name on the library’s Articles of Association and initially hosted the Library Company at his home on Pewter Platter Alley (near Christ Church). He served as a Library Company director from 1731 to 1733, and served again in 1739.

In the 292 years since that first share was issued, our list of shareholders has grown to include more than 9,800 people and institutions, including signers of the Declaration and Constitution, merchants, doctors, soldiers, scientists, artists, philanthropists, politicians, and much more.

You can read about a tiny fraction of those shareholders in our monthly Shareholder Spotlight series. And I see the impacts of all those shareholders in our directors’ minutes, our correspondence, our financial records, and much more.

The shares themselves have never truly been commodities or assets that could be sold on the open market. Library Company directors reviewed and approved each new shareholder and therefore controlled the “use and service of their Library” (as stated on a 1733 share receipt).

But Library Company shares certainly held monetary value, and you can trace those value changes while browsing various Library Company records over time.

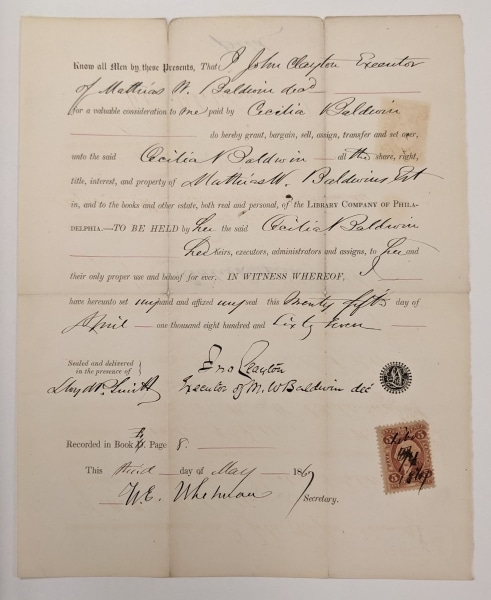

New shareholder Cecilia Baldwin Darley (1828-1909), for instance, had to purchase share #819 from the estate of her father Mathias W. Baldwin (1795-1866). The library’s directors must have approved the transfer, because she continued as a dues-paying shareholder for the next 42 years.

Image: Cecilia Baldwin receipt from Mathias W. Baldwin Estate, April 25, 1867. Library Company of Philadelphia Records (MSS00270).

Library Company directors also issued new shares to pay bills or raise money for new expenses.

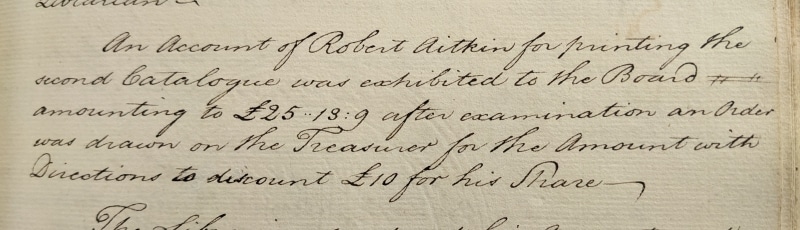

After printer and publisher Robert Aitken / Aitkin (1734-1802) printed the Library Company’s “second Catalogue” in 1775, the library’s directors paid his bill partly with a share. (He seems to have preferred the cash; he resold share #426 only two years later.)

Image: Detail from April 18, 1775 minutes. Directors Minutes Vol. 2 1768-1785. Library Company of Philadelphia Records (MSS00270).

In 1790, the Library Company issued new shares as payment for some of the workers helping to construct our first building near 5th and Chestnut Streets.

And in 1831, the Library Company gave artist Thomas Sully (1783-1872) two shares as payment when the library commissioned him to paint a portrait of James Logan (1674-1751). Sully too seems to have preferred cash. With the directors’ blessing, he sold one share to George D. Wetherill (share #992), a paint dealer, and the other to Ashbel G. Ralston (share #993), a director of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

My colleague Abigail Guidry, LCP Papers Project Digitization and Metadata Technician, is hard at work digitizing all of these records so we can provide new online access to them. We look forward to sharing more of our institutional history in the months to come.

Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this blog post do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.