Pandemic Reading: Bubonic Plague and Journal of the Plague Year

Jim Green, Librarian

This is the second of a series of blog posts about books in the Library Company’s collections about contagion and confinement, epidemics and quarantines. Read the first post on Boccaccio’s Decameron.

Just as the gilded youth of the Decameron told tales to alleviate the tedium of their self-imposed quarantine, I find writing these blogs really makes the time fly. So now let’s turn our attention to a much later outbreak of the bubonic plague, the Great Plague of London in 1665-1666. It killed a quarter of London’s population over an 18-month period, and it lived in memory as the last major epidemic of plague to strike England.

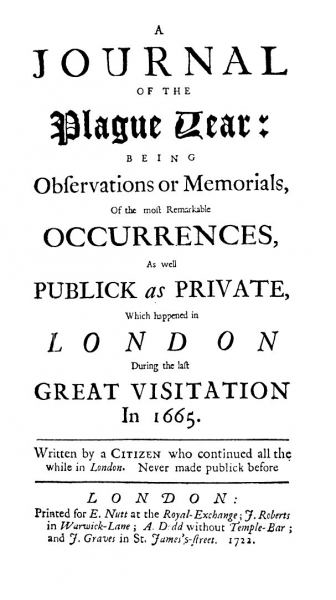

Part of that memory is due to the fact that it was memorialized in 1722 by Daniel Defoe in his Journal of the Plague Year. We think of Defoe as a novelist, because of Robinson Crusoe, but he wrote in a wide range of genres. In fact, Crusoe itself straddles generic boundaries that hardly existed then; when it was published in 1719 it was received as a travel book written by a real person called Crusoe. To this day, critics still argue over whether the plague journal is novel or an actual journal written by Defoe’s uncle Henry Foe, a saddler by trade, who really existed and unlike his nephew (born 1660) really witnessed the plague. (It is written in the first person, the author calls himself a saddler, and he identifies himself at the end as H.F.) Most likely Defoe came across his uncle’s journal somehow and edited it to make it even more life-like, or perhaps I should say novel-like.

Portrait of Daniel Defoe, National Maritime Museum, London, 17th/18th century, Unknown, style of Sir Godfrey Kneller

Title page of the original edition of Daniel Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year. Published in 1722 by E. Nutt.

It certainly has the ring of truth. It is filled with minute facts that are verifiable yet not obviously taken from any published source. Every page has vivid eyewitness details and powerful evocations of the narrator’s reactions:

[I]t is incredible and scarce to be imagined, how the posts of houses and corners of streets were plastered over with doctors’ bills and papers of ignorant fellows, quacking and tampering in physic, and inviting the people to come to them for remedies, which was generally set off with such flourishes as these, viz.: ‘Infallible preventive pills against the plague.’ Etc.

The swellings, which were generally in the neck or groin, when they grew hard and would not break, grew so painful that it was equal to the most exquisite torture; and some, not able to bear the torment, threw themselves out at windows or shot themselves, or otherwise made themselves away, and I saw several dismal objects of that kind. Others, unable to contain themselves, vented their pain by incessant roarings, and such loud and lamentable cries were to be heard as we walked along the streets that would pierce the very heart to think of.

We somehow acquired a copy of Defoe’s Journal before 1770. Since it was long out of print, it would not have been easy to come by. It is possible that it was the gift of our book agent in London, Peter Collinson. He was an avid antiquarian with an interest in the history of London and the many upheavals it had lived through, as we know from having recently acquired his copy of Maitland’s History of London filled with annotations about his own experiences and recollections.

It is equally possible that it was the gift of Franklin himself. He was an admirer of Defoe, as we know from his Autobiography, where he credits him with “a Method of Writing very engaging to the Reader, who in the most interesting Parts finds himself as it were brought into the Company, and present at the Discourse.” Of course, this raises the question of whether he could have known Defoe wrote the Journal. Again, it is not impossible. He was in London in 1724-6 working as a printer and hanging out in literary circles, where gossip about such matters was rife. But enough conjecture. It is amazing enough that we had a copy of such a rare book.

Oil portrait of Benjamin Franklin by James Reid Lambdin ca. 1880, after the original by David Martin, 1767. Library Company.

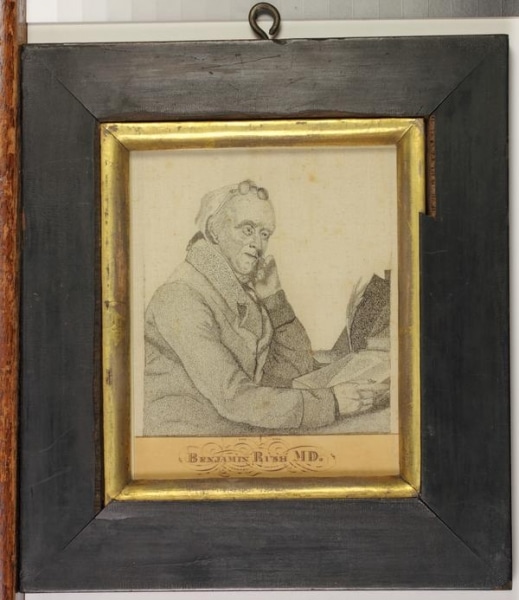

Our copy was in good company, though, not because of our collective good taste in literature, but because of the intense interest in medicine that made us the largest medical library in colonial America. James Logan’s library, enriched by the library of his brother, Dr. William Logan of Bristol, England, was a major source, but there were many others. We had works on the plague in antiquity by the Greek physician Alexander of Tralles (1549) and by Thomas Sprat (The Plague of Athens, 1683). We had works on plague medicine by Nicholas Bownd (1603) and Matthew Untzer (1615). We had a clutch of medical treatises published during and right after the London Plague by J.B. van Helmont, Gideon Harvey, William Kemp, and Athanasius Kircher. And we had the other famous eyewitness accounts: Nathaniel Hodges’ Loimologia, in English and Latin, and the English Puritan minister Thomas Vincent’s God’s Terrible Voice in the City. That was what we had back in the day. In 1869 we received Benjamin Rush’s entire medical library, and in 2017 Charles Rosenberg gave 32 titles from his library just on plague, not counting hundreds more on smallpox, yellow fever, and cholera, which will the subject of future posts.

Portrait of Benjamin Rush on silk gifted to the Library Company in 1869 by James Rush

So, we were and still are the place to go to find out about plague. For now, I’ll leave you with Defoe’s description of the scene when the people realized the plague had passed:

Going one day through Aldgate, and a pretty many people being passing and repassing, there comes a man out of the end of the Minories, and looking a little up the street and down, he throws his hands abroad, ‘Lord, what an alteration is here! Why, last week I came along here, and hardly anybody was to be seen.’ Another man—I heard him—adds to his words, ”Tis all wonderful; ’tis all a dream.’ ‘Blessed be God,’ says a third man, and and let us give thanks to Him, for ’tis all His own doing, human help and human skill was at an end.’ These were all strangers to one another. But such salutations as these were frequent in the street every day; and in spite of a loose behaviour, the very common people went along the streets giving God thanks for their deliverance.

…indeed we were no more afraid now to pass by a man with a white cap upon his head, or with a cloth wrapt round his neck, or with his leg limping, occasioned by the sores in his groin, all which were frightful to the last degree, but the week before. But now the street was full of … these poor recovering creatures.

I shall conclude the account of this calamitous year therefore with a coarse but sincere stanza of my own, which I placed at the end of my ordinary memorandums the same year they were written:—

A dreadful plague in London was

In the year sixty-five,

Which swept an hundred thousand souls

Away; yet I alive!H.F.

Read the Journal of the Plague Year.