Pandemic Protest, Pandemic Riots

Jim Green, Librarian

Over the previous seven installments of Pandemic Reading, I’ve often mentioned breakdowns of the social order associated with historical pandemics. At a Zoom conference in early May called “Pandemic: Creating a Usable Past,” Charles Rosenberg said that pandemics are a sort of stress test, highlighting weaknesses, not just in the health care system, but throughout society. The aptness of this observation became painfully clear in the month that followed. The Covid-19 pandemic exposed the racism, inequality, and ruling-class corruption that are tearing our nation apart, and that led to the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police, and to the weeks of protests, rioting, and police violence that followed. In much the same way, the 1793 yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia exposed the racism of the city’s supposedly benevolent elite, which prompted a response from Black community leaders Absalom Jones and the Richard Allen that has been called the first pamphlet of Black protest.

Today our leaders insist on a clear distinction between peaceful protest and rioting; however, in reality, protest and rioting run on a continuum along the fault lines that Covid-19 has exposed. As Martin Luther King, Jr. said, “riots are the language of the unheard.” In antebellum Philadelphia riots were endemic, sometimes connected to protest, but mostly they were simply riots. The rioters were all white, and their victims were mostly free Blacks, making these riots a significant expansion of the systemic violence against Black people in America that has continued almost without a break for hundreds of years.

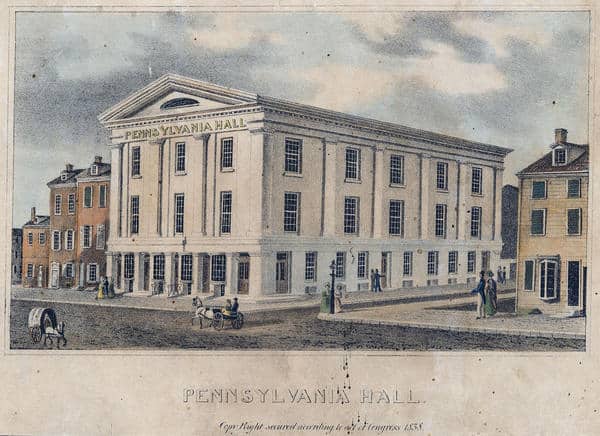

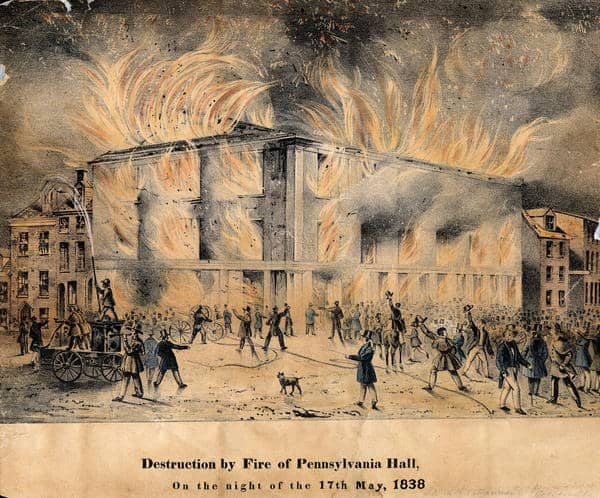

The most famous riot of the period was the burning of Pennsylvania Hall on May 17, 1838. The hall had just been built by the Pennsylvania Abolition Society as a venue for their public meetings, a “temple of free discussion” of antislavery, women’s rights, temperance, and other reforms. Four days after it opened it was torched by a mob, said to have been organized by a group of “gentlemen from a certain section of the country.” What angered the rioters was not only what the speakers said but also the fact that so many of them were women and African Americans, and that Blacks and whites sat together in the audience without separation. The police made no effort to intervene, and the several fire companies that converged on the site refused to fight the fire, instead pointing their hoses at the houses around the hall. In the days that followed rioters also torched the Friends Shelter for Colored Children and damaged the AME Mother Bethel Church.

J.C. Wild, Pennsylvania Hall, hand-colored lithograph (Philadelphia, 1838). Library Company digital collections. Before the fire.

J.C. Wild, Destruction by Fire of Pennsylvania Hall, hand-colored lithograph (Philadelphia, 1838). Library Company digital collections. During the fire, showing the fire companies’ refusal to train their hoses on the fire.

John Sartain, [Destruction of the Hall] Drawn from the spot. Mezzotint (Philadelphia, [1838]). Library Company Digital Collections. Sartain’s view focuses more on the shady-looking mob.

The mob was emboldened by efforts of the anti-abolition Democrats to amend the Pennsylvania constitution to disenfranchise property-owning free Blacks in the state, who had had the right to vote since 1776. Most Pennsylvanians were initially against disenfranchisement, even many Democrats, who had long supported extension of voting rights more generally. Party leaders came to embrace disenfranchisement as part of a strategy to appease the southern wing of their party and even, some said, to preserve the Union. In the Constitution Reform Convention of January 1838, they succeeded in placing the amendment on the ballot in the November elections. Just a few days later, Pennsylvania’s Supreme Court ruled that African Americans had already been disenfranchised in a 1795 high court ruling. No written record of that proceeding remained, but the lawyer arguing the case claimed to remember it “perfectly.” The Democrats’ strategy here was to prevent Blacks from voting against the amendment that would disenfranchise them. One Philadelphia Democrat warned that “in twenty-four hours from the time that an attempt should be made by blacks to vote, not a negro house in the city or county would be left standing”.

The response of the Black community took the form of another landmark protest pamphlet, The Appeal of Forty Thousand Citizens, Threatened with Disenfranchisement, by Robert Purvis, which was published in April, shortly before Pennsylvania Hall was to open. Like Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, Purvis eloquently countered the lies and misconceptions about the Black community spread by the Democrats and cited (real) legal precedents and state documents to show that the founders intended all free men regardless of race to have voting rights. The proposed amendment, he wrote, has “laid our rights a sacrifice on the altar of slavery.”

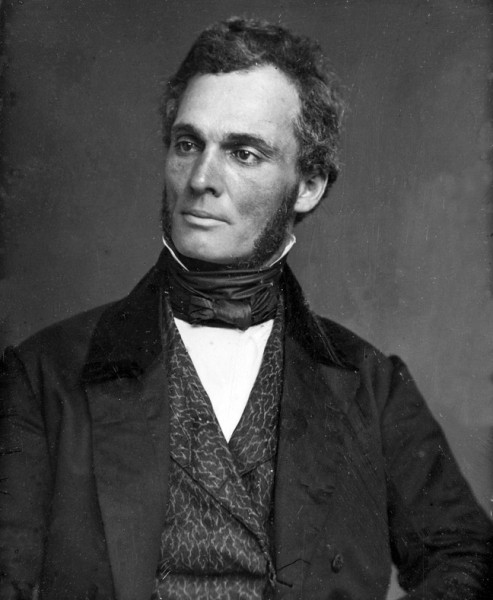

Portrait of Robert Puvis by an unknown photographer taken much later in his life. Courtesy of the Boston Public Library.

Thus, by bogus legal maneuverings and naked threats, the Black vote was suppressed, and the amendment was ratified in the fall election by a margin of just 1,212 votes, a small fraction of the number of African Americans who had previously been eligible to vote. Shamefully and tragically, Pennsylvania African Americans lost their voting rights.

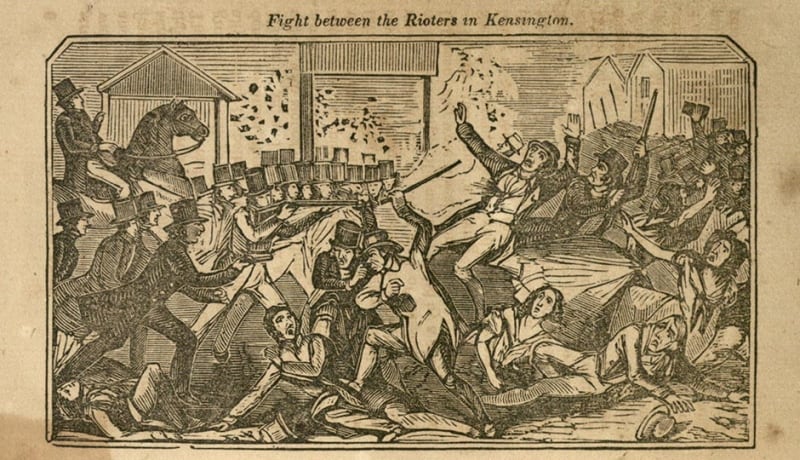

The second major riot in Philadelphia during these troubled years took place in 1844 and was known as the Bible riot. An influx of Catholic immigrants from Ireland in the early 1840s gave rise to the anti-immigrant Native American Party, composed largely of Protestant Scots-Irish. Native-born whites hated the Irish almost as much as they hated free Blacks. As historian Noel Ignatiev argued in his book How the Irish Became White, the Irish were racialized in cities like Philadelphia. If they weren’t considered Black, they certainly weren’t viewed as white. In 1844 tensions between Protestants and Catholics focused on the issue of whether the King James or the Douay Catholic Bible should be read in public schools. In a public assembly in Kensington, just north of the city proper, Protestant speakers were heckled by Catholics, words were exchanged, then blows, then gunshots. The first to die was a Protestant named George Shifler. In the lithograph below, he is shown wrapped in the American flag in a posture of martyrdom. In the riots that followed, several Catholic Churches were burned down.

Burning of St. Augustine’s church. Woodcut in John B. Perry, A Full and Complete Account of the Late Awful Riots in Philadelphia (Philadelphia, 1844).

John L. Magee, Death of George Shifler in Kensington. Hand-colored lithograph, Philadelphia, [1844?]. Library Company Digital Collections.

Rioters in Kensington, woodcut in John B. Perry, A Full and Complete Account of the Late Awful Riots in Philadelphia (Philadelphia, 1844).

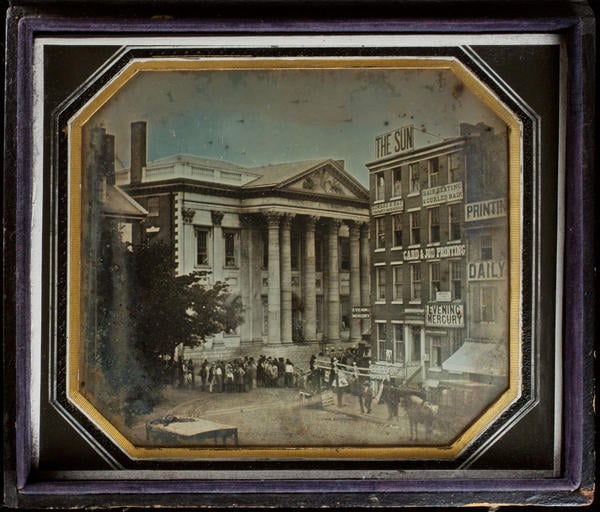

The governor decided to call out the militia. This daguerreotype shows them mustering in front of Girard’s Bank (formerly First Bank of the United States) on Third Street near Chestnut, on May 9, 1844. By then the riots had cooled down.

W. & F. Langenheim, “North-east corner of Third & Dock Street. Girard Bank, at the time the latter was occupied by the military during the riots.” Daguerreotype, May 9, 1844. Library Company Digital Collections.

When the riots resumed in July, the military presence was even greater, with cannons, cavalry, and an estimated 5,000 soldiers. What had begun as a conflict between Protestants and Catholics morphed into a fight between the military and the public. This was the first time U.S. government troops fired on the people of Philadelphia. But it was not the last.

Scene from the riots in July 1844. Woocut in John B. Perry, A Full and Complete Account of the Late Awful Riots in Philadelphia (Philadelphia, 1844).

In addition to these two riots, there were bloody anti-Black riots almost every year throughout the 1830s and 1840s that were simply manifestations of white hatred. They all took place in a predominantly African American neighborhood near the southern border of the city and encompassing the suburbs of Moyamensing and Southwark. In 1834 the spark was a fight over who could ride on a merry-go-round in a park at Seventh and South. In 1842 Irish Catholics attacked a black parade along Lombard Street celebrating the 8th anniversary of the abolition of slavery in Jamaica. And in 1849 a rumor that the owner of a hotel or tavern on Sixth near South called the California House was living with a white woman was reason enough to have a riot. These are only the biggest of the many riots. In each case the result was fighting in the streets and the destruction of Black houses, businesses, churches, and lives.

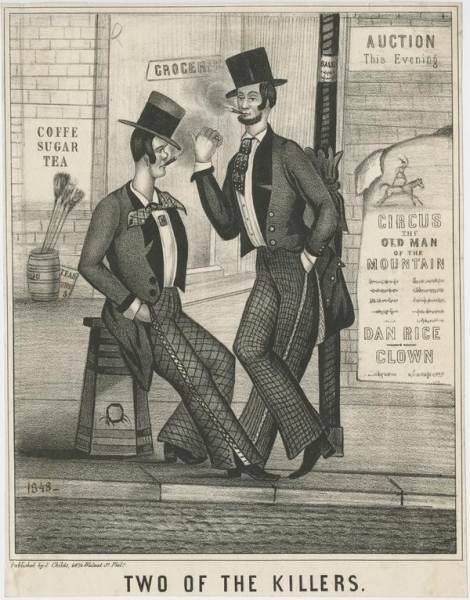

The 1849 California House riot made its way several times into fiction, as if to underscore the fact that violence against Black people was now so systemic and routine that it had become a part of popular culture. In 1850 novelist George Lippard, whose best-selling 1844 novel The Quaker City exposed the corruption and hypocrisy of the Philadelphia elite, published a lesser-known novella based on the 1849 riots called The Killers, after the gang that attacked and burned California House. Here is a contemporary lithograph showing gang members dressed in the height of fashion.

John Childs, publisher. Two of the Killers. Lithograph, Philadelphia, 1848.

Characters like these are now familiar to us thanks to the 2002 movie The Gangs of New York. Here is a still of Daniel Day Lewis as nativist gang leader Bill Cutting dressed in the same style. And here is the official trailer:

Rival fire companies allied with the gangs joined the fray, along with the police and the militia. Here is an illustration of the riot from the book:

The plot is incoherent, full of sinister characters and fantastic coincidences. Lippard recycled the story four times under three different titles. Here is a link to one of those versions called The Bank Director’s Son. It makes for great pandemic reading.

The California House riot (along with elements of the 1834 riot) was also incorporated into Frank Webb’s The Garies and their Friends (London, 1857), the second novel written by an African American. It tells the story of Georgia plantation owner Clarence Garie and his enslaved mistress Emily, who move together to Philadelphia hoping to marry legally and raise their family in freedom. Their hopes are cruelly dashed by the reality of northern racism. Their only true friends are a Black carpenter named Ellis and his family. Both families are ensnared in a plot by the evil white lawyer Stevens to incite a riot in the Lombard Street neighborhood, in order to drive down property values so he can acquire the real estate. In the course of riot (spoiler alert!) Garie is shot dead, Emily dies in childbirth, and Ellis, on his way to warn the Garies, is beaten by the mob and left so brain damaged he will never work again.

Our former curator of African American history, Phil Lapsansky, played a major role in reviving interest in this astonishing novel, which has become a standard text in American literature classes. And just a few years ago our fellow Mary Maillard revealed how closely the novel follows the real-life story of the Webb family, in her brilliant article “Faithfully Drawn from Real Life”: Autobiographical Elements in Frank J. Webb’s The Garies and Their Friends,” in The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 137:3 (July 2013).

Here is a link to the original edition of The Garies and their Friends.

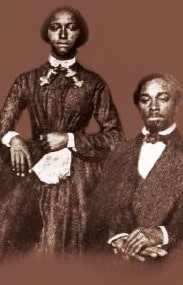

Reproduction of a daguerreotype portrait of Frank J. Webb and his wife Mary E. Webb. The original is at the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center in Harford, Connecticut.

The rioting that was endemic in Philadelphia in the 1830s and 1840s coincided with epidemics of cholera in 1832 and 1849 and of typhus in 1835-37 and 1847-48. In The Garies, the man who murdered Clarence Garie confesses his crime while delirious with typhus, precipitating the suicide of Stevens and the recovery of the property he stole from the orphaned Garie children. The destruction of Pennsylvania Hall coincided not only with a typhus epidemic but also with the Panic of 1837 and the onset of a depression that lasted for six years. Likewise, today we are experiencing a concatenation of disease, economic collapse, and social conflict. The idea that epidemics are a stress test revealing the weaknesses in the social order seems to make more sense every day.

![John Sartain, [Destruction of the Hall] Drawn from the spot. Mezzotint (Philadelphia, [1838]). Library Company Digital Collections. Sartain's view focuses more on the shady-looking mob. John Sartain, [Destruction of the Hall] Drawn from the spot. Mezzotint (Philadelphia, [1838]). Library Company Digital Collections. Sartain's view focuses more on the shady-looking mob.](https://librarycompany.org/wp-content/uploads/JPG_digitool_129971_Destruction-of-the-hall.jpg)

![John L. Magee, Death of George Shifler in Kensington. Hand-colored lithograph, Philadelphia, [1844?]. Library Company Digital Collections. John L. Magee, Death of George Shifler in Kensington. Hand-colored lithograph, Philadelphia, [1844?]. Library Company Digital Collections.](https://librarycompany.org/wp-content/uploads/JPG_digitool_65090_Death-of-George-Shifler-in-Kensington.-Born-Jan-24-1825.-Murdered-May-6-1844.-432x600.jpg)

![[Election night mob] [graphic]. [Election night mob] [graphic].](https://librarycompany.org/wp-content/uploads/JPG_Islandora_2780_Election-night-mob-graphic..jpg)